Daring to Feel

Just before the New Year, in an article that shared my devotion to qigong, I mentioned how beneficial it would be if we all arrived on this planet with a “Homo Sapiens Owner’s Manual” that could help us live our best life physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Since then, I’ve been thinking a lot about what else needs to be included, and another list-topper would be guidance on how to work with emotions.

It wasn’t until my 50s that I discovered I was stuck in patterns of emotional evasion and repression. Because I’ve always been effusively expressive, I truly believed that I was in close touch with my feelings. I didn’t see that since childhood I’d been trying to run from, suppress, or edit all of my painful emotions.

I think some of this relates to being the daughter of two Holocaust survivors. Somehow my little girl self made an unconscious promise to always be happy and never add to my parent’s anguish. As I got older, I marginalized my pain because my bar for suffering was set so high. I knew that none of my upsetting experiences could ever come close to what my mother and father had endured.

Myra’s parents, Mendek and Edith Rubin, circa 1998

Although my parents rarely spoke of their past growing up, I recall one occasion when I complained to my mother about a dinner I disliked. She immediately burst into a tirade about how during the war she felt like the luckiest person on earth when she found a few pieces of filthy potato peels that had been ground into the floor. I was around seven years old at the time, and I don’t remember ever complaining about a meal again.

But there was one feeling I never had any success trying to repress, and that was fear. I lived in a constant state of low-grade terror that could become overwhelming at the slightest provocation. Trying to escape from fear was like running away from an angry bear in the forest—I became its panicked quarry.

In her best-selling book, Good Inside, clinical psychologist and parenting expert Dr. Becky Kennedy explains why trying to evade difficult feelings never ends the way we want it to. “The more you avoid distress or will it to go away, the worse it becomes. Our bodies interpret avoidance as confirmation of danger, and it triggers our internal alert system. The more energy we use to push emotions like anxiety or anger or sadness away, the more powerfully those emotions spring back up.”

Learning to embrace all of our emotions is an important part of feeling safe on planet earth. Dr Becky explains that our bodies won’t allow us to feel relaxed when we believe that the feelings inside us are wrong, scary or overpowering. Trying to make them go away only fuels our distress. “Ultimately,” she writes, “This is how anxiety takes hold within a person. Anxiety is the intolerance of discomfort. It’s the experience of not wanting to be in your body, the idea that you should be feeling differently in that specific moment.”

A recent national survey found that 73% of Americans rated happiness as their most important goal in raising children, yet Dr. Becky believes that when we want our kids to be happy and urge them to “cheer up,” we’re actually encouraging them to avoid feelings of fear and distress. “When we focus on happiness,” she writes, "We ignore all the other emotions that will inevitably come up throughout our kids’ lives, which means we aren’t teaching them how to cope with those emotions.”

Dr. Becky believes a much more important goal for parents is to help their kids relate to pain and hardship more skillfully—to learn that they are very capable of getting through tough times, so they don’t need to avoid them. One of the reasons I’m such a huge fan of Dr. Becky is that she’s teaching people of every age how to build emotional resilience hand-in-hand with self-acceptance and self-trust. Her aim is to help break intergenerational cycles of emotional dysregulation.

Decades ago, when my children were born, I had the opportunity to see my mother in action with her grandchildren, which gave me a very revealing glimpse into how I had been raised. Every pain, cry or cough was reacted to with gasps of worry. To my mother, being sad or ill was a calamity. If my child’s upset wasn’t immediately quelled, her hysteria would build. No wonder I learned to quickly flee discomfort at a very young age, and why I parented with a diluted form of this same type of anxiety.

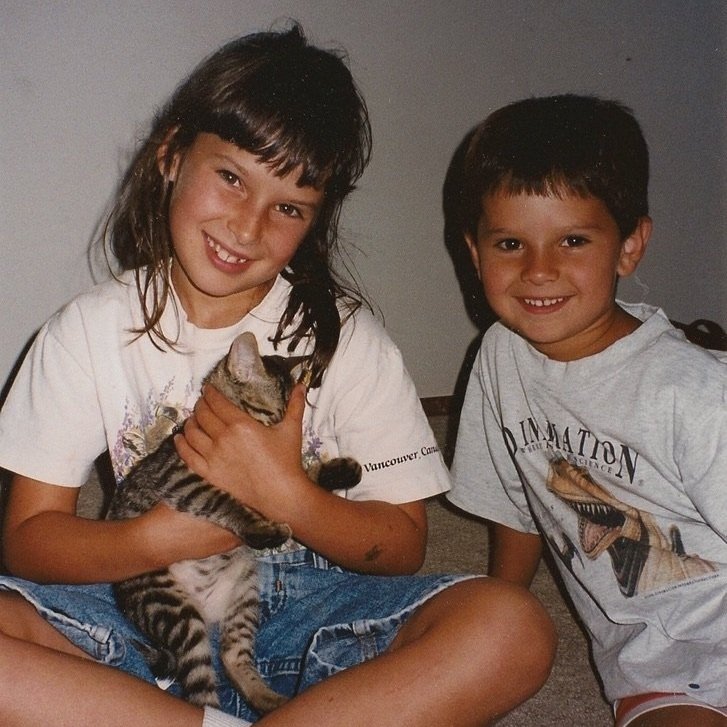

Myra’s children, Marea and Jeff, circa 1996

Over the holidays, I loved watching my daughter care for her toddler. Thankfully, Marea doesn’t view upset as a tragedy that needs to be overcome as soon as possible. When her son cries, she holds him and comforts him, but she doesn’t try to quiet or distract him. She believes that it’s important for him to fully feel whatever emotions arise—to learn to ride waves of sadness, fury, or overwhelm until they naturally ebb. She calmly witnesses his pain and stays with the outburst for as long it lasts.

Unlike my grandson, I only began sitting with sadness and discomfort in middle age. I’m still learning that just as day turns to night and the seasons change, pain will always come and go. It’s a perfectly acceptable and ordinary part of life.

In a Psychology Today article titled “Suppressing Emotions Can Harm You—Here's What to Do Instead,” psychotherapist Katherine Cullen explains that one of the reasons we don’t want to ignore our emotions is that they’re meant to communicate important information about our internal and external environments to ourselves and to others, and to mobilize us for particular behaviors. For example, anger signals that a boundary, value, or rule has been violated, and mobilizes us to defend or attack. Fear signals threat or danger, and mobilizes us to freeze or flee. Guilt signals remorse and motivates us to make amends.

Cullen says that the “primary human emotions”—anger, sadness, fear, joy, disgust and surprise—are actually present from the moment we are born, while “social emotions”—shame (feeling that one is bad), guilt (feeling the one has done something bad), embarrassment and pride—emerge after about 18 months.

Emotions are such a central part of being human that trying to suppress or deny them isn’t only ineffective, it increases our stress levels and ups our risk of heart disease, hypertension, anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. But Cullen also points out that it’s unhealthy to express our emotions in unbridled ways.

Learning to stop running from feelings and work with them skillfully has been one of the most essential cornerstones in my own journey of healing and personal growth. After years of practice, I’m finally getting better at it and am beginning to reap the rewards: more self-awareness, less anxiety, a quieter mind, and feeling safer in my body.

Now, when I feel a difficult emotion arise, instead of trying to escape it, I consciously turn toward it, as if I’m gently tugging on the reins of a horse so it won’t gallop away. Aloud or in my mind, I name the emotion and welcome it: “Hello fear. You are welcome here. You have my attention.”

When I welcome a feeling as soon as I notice it, it doesn’t need to scream as loud to get my attention. This practice also helps me better differentiate between myself and the fear, because I shift from, “I am afraid,” to more of a sense that I am what’s solid and the fear is simply a temporary visitor.

I find it helpful to breathe deeply and slowly to calm my nervous system as I tune into what the emotion actually feels like in the moment. My aim is to stay present in my body—to not get caught up in judgments, explanations, stories, worries or action plans to alleviate what my mind believes “caused” the emotion.

Sometimes I comfort myself as I would a small child, with touch and soothing words. At other times, I’ll discharge the energy physically—through shaking, growling, or vocal sighs. Often, when big emotions come and then finally pass through, I’ll feel a sense of elation, as if I just accomplished something quite daring and challenging, like skydiving.

Finally, I try to view difficult feelings as friends, not foes. I know that they’re part of my body’s natural way of adjusting to change and processing difficult experiences, and that they often serve my highest good by communicating valuable information that helps me learn, grow, and set appropriate boundaries.

Working with emotions skillfully is a huge topic and there are many different approaches. Because this subject feels so important to me, I’m extra-excited about our first Quest for Eternal Sunshine free workshop of the year, “Stop Running from Feelings—Tools to Embrace Every Emotion” on January 20, which will be taught by mindfulness and meditation teacher, Katie Dutcher.

As the sage Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh said, “If we face our unpleasant feelings with care, affection, and nonviolence, we can transform them into a kind of energy that is healthy and has the capacity to nourish us. By the work of mindful observation, our unpleasant feelings can illuminate so much for us, offering us insight and understanding into ourselves and society.”