One in a Million

Bill at the Museum of Tolerance in 2019 at the age of 95

A few months ago, I participated in a wonderful online event with the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles for Quest for Eternal Sunshine. Afterwards, the museum let me know that a Holocaust survivor and frequent lecturer at the museum—a man named William Harvey—wanted to connect with me. A few days later, I received a lovely introductory email from Mr. Harvey telling me how much he’d enjoyed my presentation. He asked to speak further about my father’s story, and also mentioned that he’d be turning 96 the following day, May 20, 2020.

Bill and I became fast friends over the phone. Sharp as a college professor, Bill is an engaging conversationalist with an inspiring story of survival and success. It also turns out that he’s a bit famous. Soon after immigrating to America in 1946—an orphan with no money, skills, or knowledge of English, his only possessions the clothes he was wearing—Bill became a sought-after hair stylist to some of the biggest stars in the country.

At twenty-two, he’d been taken in as an errand boy by the prestigious Madam Fischer’s Beauty Salon on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, earning $24 per week. The salon’s clients included Mae West and the entire Gabor family: “Mama Gabor” and her three daughters. Without any training, just learning on the job, Bill displayed an extraordinary talent for styling hair, and quickly attracted famous clients of his own, including Mary Martin, and later, when he relocated to Los Angeles in 1950, Judy Garland.

Bill was one of ten Holocaust survivors featured in a comprehensive multimedia story put together by the Hollywood Reporter on the 70th anniversary of liberation. Created in collaboration with Steven Spielberg and the Shoah Foundation, “Hollywood’s Last Survivors” opened with Bill’s story and closed with Dr. Ruth Westheimer.

My affection for Bill grew quickly, partially because he reminds me so much of my father. Despite living through terrible horror and loss, they both became men overflowing with love and wisdom.

Bill credits his open heart to his mother, Rozali, “the kindest woman I’ve ever known.” Bill’s father was unwell, so his mother had to raise and support six children on her own. Bill was born eight years after his five siblings: four sisters, and a brother who died at eighteen. The baby of the family, Bill was born when his mother was already in her early forties. The two of them were extremely close.

“Growing up, our home in Czechoslovakia had no indoor plumbing or electricity,” Bill told me. “In addition to going to the farmer’s market to purchase all of our food and cooking delicious meals for six children, my mother was a talented designer who sewed for a living. She often worked so late into the night that she’d fall asleep over her sewing machine, never making it to bed. She never once complained, and I knew without a doubt how much she loved me. She had so much love to share.”

Bill’s mother, Rozali, at 20 in New York in 1902

Four of Bill’s siblings: Gilbert, and three of his sisters—Giselle, Margaret, and Elizabeth—in 1920, before Bill was born

Bill at twelve in Czechoslovakia

In early 1944, while Bill’s frail father was walking down the street with his cane, he was attacked by German soldiers and beaten so severely that he died from his injuries a few days later. Soon after, Bill, his mother, and his two sisters who still lived at home were forced to relocate to the ghetto under appalling conditions. Six weeks later, all Jews in the ghetto were rounded up and forced into tightly packed airless cattle cars. After five horrendous days, they arrived at Auschwitz, where Bill’s mother was sent to the gas chambers. Nineteen-year-old Bill and his two sisters were sent to work camps.

Bill barely survived the war. Days before liberation—weighing only 72 pounds after enduring a year of starvation and brutal forced labor, with a crushed foot he couldn’t walk on—Bill was so frozen from cold that he had been left for dead amid a pile of corpses. Eventually, he would discover that his sisters had survived as well.

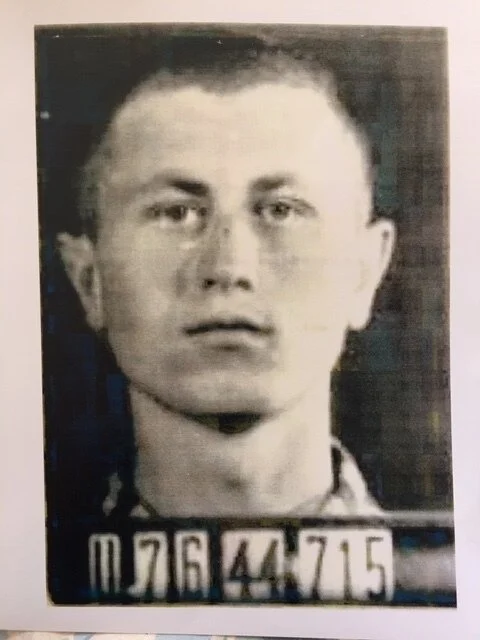

Bill in Buchenwald at 19, thirteen days after being taken to Auschwitz

Soon after liberation, Bill had a breakdown. “I was hospitalized for three months, crying almost the entire time. I couldn’t believe that my mother wasn’t coming back. My tears just wouldn’t stop. But I eventually decided that I was too young to give up my whole life. I could cry endlessly, but it wouldn’t change anything.” Bill concluded that his best revenge would be to make a success out of his life—“to turn all the negatives into positives.”

Bill also made the decision: to stop hating his enemies. “The definition of hate is the loss of love. If you do not love, you are not living—you are merely existing. So, I had to learn how to forgive. Learning to accept my fellow man was the hardest challenge. It took a lifetime of practice, but I learned to do it.”

I asked Bill how it was possible not to hate those who destroyed the people he loved most in the world. What was his secret?

“I had to be willing to forgive,” Bill told me, “Because if I didn’t, I’d be destroying my own life. I know other survivors who still suffer every day, believing God did this terrible thing. But I don’t believe God did anything terrible to anybody. God is love. I’ve never blamed God for the Holocaust. God created human beings, not puppets. If God were able to control us, then we wouldn’t be human beings.”

The best part of his life, Bill told me, is helping people who are less fortunate. “My thirty-five-year-old neighbor is blind and has been in a wheelchair with MS for seventeen years. I help her financially, and in every way I can. Now that we’re in the pandemic, I call her a couple of times a week, and she tells me, ‘Mr. Harvey, when I hear your voice, you light up my day.’ There is no greater gift in life than that. You know Myra, no matter our financial success, we are born to this world with nothing and we take nothing with us when we go.”

When I asked Bill what he’d thought about Quest for Eternal Sunshine, he told me that he hadn’t been able to read it because he is blind. We agreed that I’d send him CDs of the book, and then circle back after he listened.

“Myra!” he excitedly exclaimed on our next call, “I was on the same ship as your father from Germany to New York, the Marine Perch! Can you believe it?”

I was incredulous—the odds almost impossible—but Bill was certain. The Marine Perch left Europe on August 22, 1946, and my father had always said the trip took ten days. The arrival date of August 31 was etched in Bill’s memory. The math worked.

“There was only one Marine Perch,” Bill told me, “an army boat, not a big one. I couldn’t stay below because the rooms were very small and filled end-to-end with bunk beds. I was claustrophobic and the seas were rough. Everybody was seasick. I never slept in my bunk. Most of us stayed on up on deck and slept in the lifeboats.” My Aunt Bronia had told me the same thing about her journey to America—how the seas were so rough she felt seasick the entire time. Even though it was the first time she’d ever seen oranges and bananas, and desperately wanted to taste them, she felt far too awful to take a bite.

Ship Roster: The page of the Marine Perch ship roster that lists Mendek and his sister Bronia as passengers

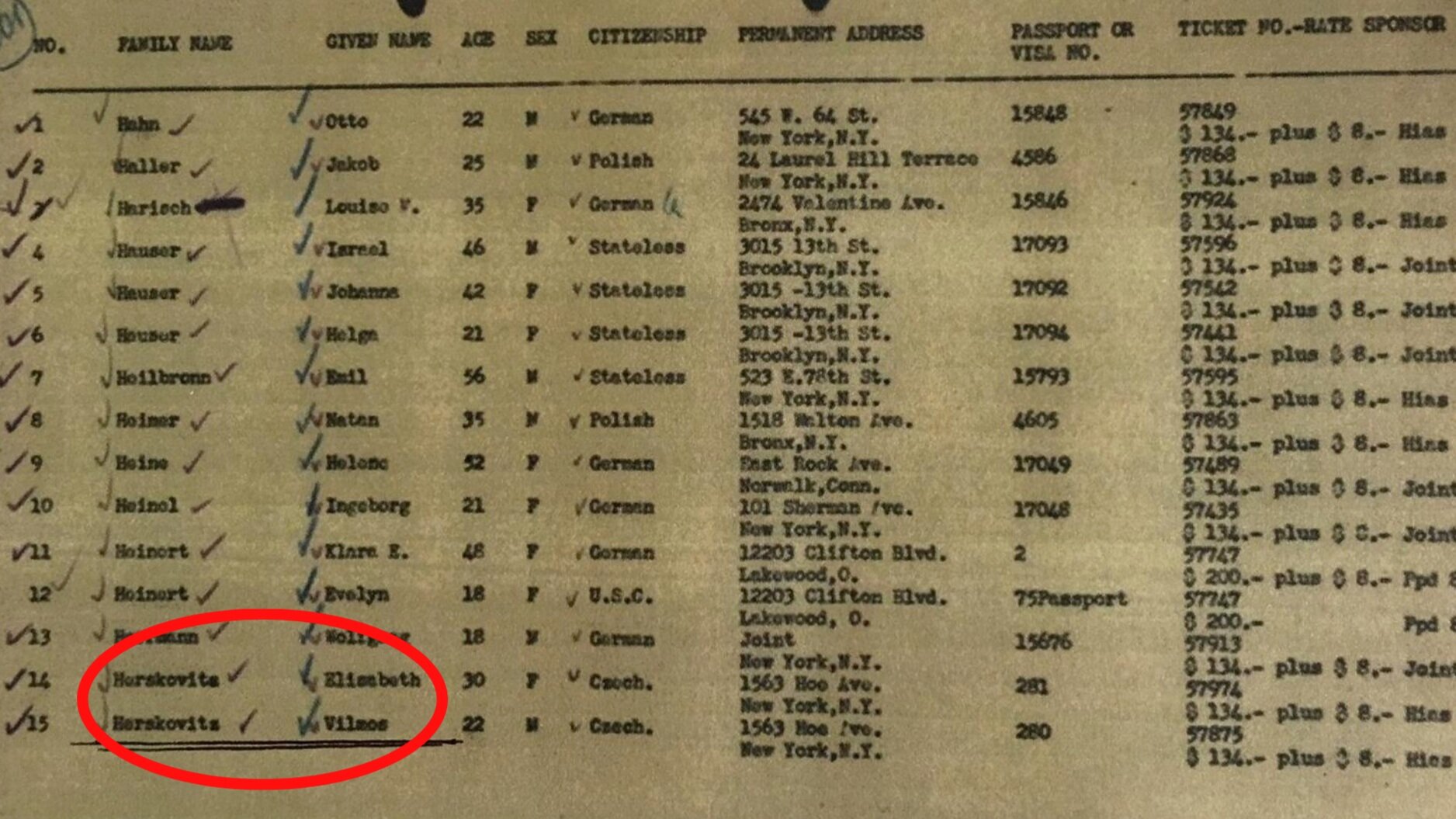

Ship Roster: The page of the Marine Perch ship roster that includes Bill and his sister Elizabeth’s names (Bill’s last name was Herskovitz until he changed it to Harvey)

Bill was certain he’d met my father. “I am a gregarious person and I met everybody on that ship. There was nothing else to do but talk. There were a lot of Polish boys, and I spoke to every one of them. We were always on the deck, and I’m positive that Mendek was there, too.” Bill and my father were the same age, born four months apart. Born in May 1924, Bill was 22 when the ship docked in America; my father turned 22 a few weeks later. I continue to be amazed by this astonishing—perhaps magical—coincidence!

There is no way to do justice to Bill’s incredible life story in one essay, but thankfully, much of it was captured on video by the Shoah Foundation. Conducted in April 1995, the interview was the first time Bill had ever shared his emotional story, even with immediate family. He’d kept silent for a full half century because he didn’t want his loved ones to know about the horrors he’d lived through, and also because he preferred to forget those terrible memories. Like my father, instead of dwelling on the past, Bill tries to make each new day a happy one.

Toward the end of the Shoah Foundation interview, Bill’s wife, two daughters and two of his grandsons were introduced. One of his daughters said, “My dad is the best. No one else comes close. He’s one in a million. He really is the most giving person, and never expects anything in return. Not just with his family. With everybody.”

Bill and June on their wedding day, 1953

Bill, his wife June, and their two young daughters, Wendy and Laurie

Bill’s beloved wife of forty-two years died of cancer just a few months after that interview. Despite missing her every single day, and his eventual loss of vision, Bill assures me that he is doing okay during this time of forced isolation, although he wishes he could see his family and continue lecturing at the Museum of Tolerance and in local schools.

Bill is financially secure, having retired from the beauty industry in his mid-fifties to move into a second successful career, this time in real estate. His two daughters call him every day, and his four grandsons call regularly—both to check in on him and to ask for his sage advice. Bringing Bill much delight is his beautiful infant great-granddaughter, Rozali, named in honor of the mother he so adored and admired.

“I enjoy every single day God gives me,” my new friend assures me. “Happiness is what you make for yourself. Nobody else can make it for you. I’m 96 and I’m a great-grandfather. Does it get any better, Myra?”