Expanding Our Perspective

Growing up, my parents were psychological and spiritual explorers. On an avid quest to heal their deep emotional wounds, they experimented with many different therapies that were popular in New York City in the 1960s—Primal Scream, Rational therapy, Gestalt therapy, Feldenkrais therapy, hypnotherapy, and all types of encounter groups.

My parents’ search continued until 1970, when they became members of a New Age spiritual group that promised a clear pathway to healing and personal evolution. Loving the camaraderie and support of converging with like-minded people, the community soon became the epicenter of our family’s life.

What started as a small group of spiritual seekers quickly grew into a sizable organization, and my parents became part of the top-level leadership circle. We eventually relocated to a house we built on the organization’s property in the countryside, leaving behind our entire life in Brooklyn—our home, school, friends and family.

Far left: Myra’s parents, Edith and Mendek, taking part in a marriage vow renewal ceremony in their spiritual community in the mid-1970s

After seven years, when I was thirteen, my parents abruptly exited the community under extremely painful circumstances, leaving our family reeling and disoriented. Eventually, when my mother and father regrouped emotionally, they resumed their spiritual explorations.

For years, my parents enthusiastically embraced a rotation of gurus and spiritual teachers who promoted various ideologies, and they were always eager for me and my sister to embrace them as well. But just as our interest was finally piqued, my parents inevitably moved on to someone new. By the time I left home for college at the young age of 16, I was suffering from belief system whiplash with the accompanying symptoms of disillusionment, cynicism, and confusion.

Despite it all—or maybe because of it—I still had a powerful need to make sense of the world and my place in it. I yearned to find meaning and some type of spiritual connection that felt authentic and everlasting.

It was this vacancy deep within that motivated me to petition the University of Vermont to allow me to create an independent major called “Human Perspectives”—a multidisciplinary study of anthropology, sociology, philosophy, and religion. My hope was that if I was able to learn about varied perspectives through which different human cultures had viewed the world, I might be able to isolate some universal truths. One of my goals was to decipher what distinguishes a belief system from a religion, and a religion from a cult.

Myra while living in India, 1982

My studies took me to India for a wildly mind-opening semester abroad, after which I transferred to UC Berkeley and switched my major to politics and economics. My plan—to go to graduate school and have a career in international relations—was ambushed by my love of living on a farm in Carmel Valley with my soon-to-be husband, Drew. For the next decade, my spiritual life and cross-cultural curiosity took a backseat to nurturing our fast-growing business and two young children. But that changed when I met Katherine Thanas, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest, and became her dedicated student for eighteen years.

Katherine was serious, wise, and humble. Her teachings were focused on what anyone could experience directly with their own body and mind—no leaps of faith required. I trusted her completely, and greatly appreciated the calm I experienced in her presence.

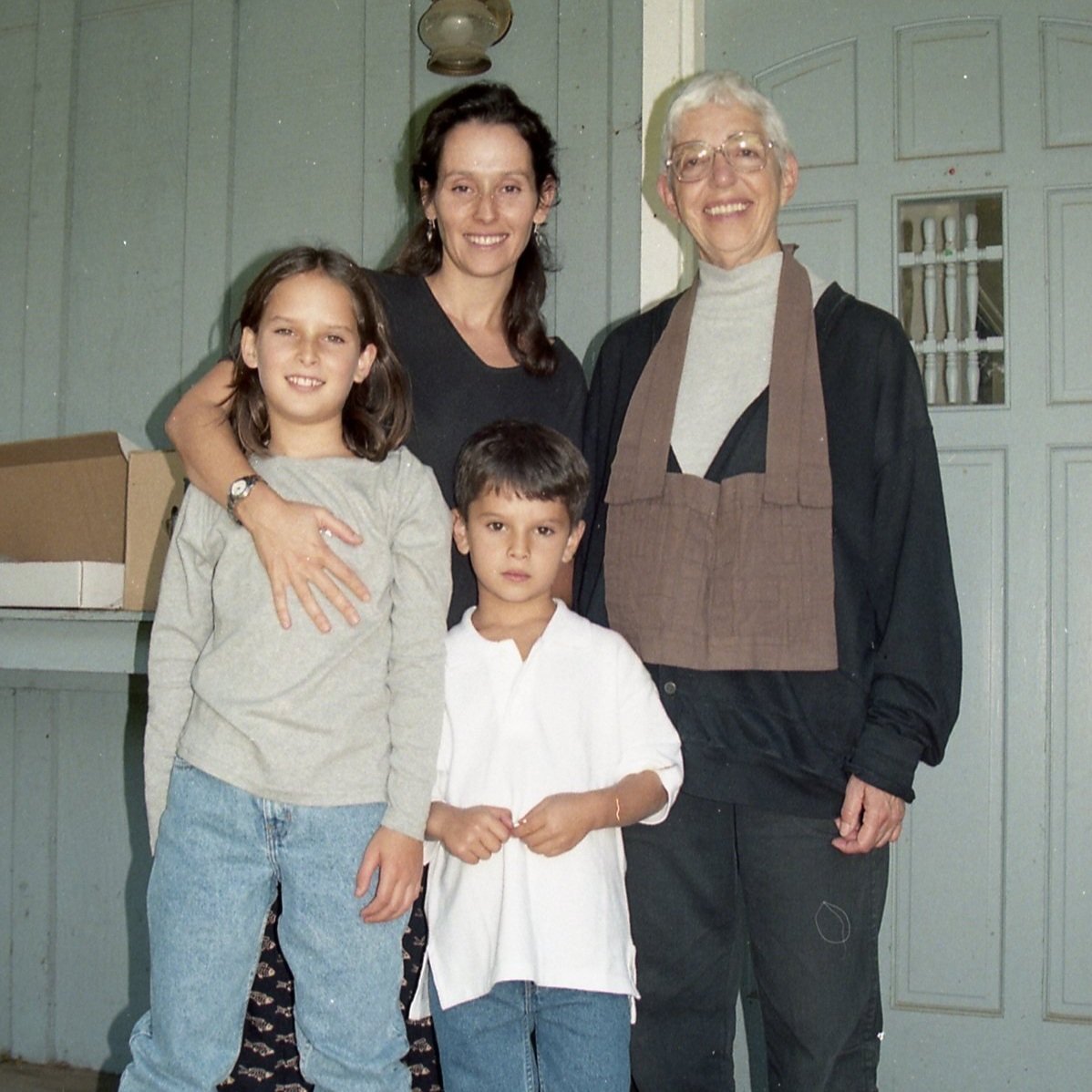

Myra and her children with Katherine Thanas, circa 1996

Katherine taught her students a lot about perspective. In a book compiling wisdom from her lectures, The Truth of This Life: Zen Teachings on Loving the World as It Is, she explained, “I’m sitting here and can only see the room from this perspective. Those of you who are sitting there can’t see the room from here. It is inevitable that we all have partial views. That’s what we call being a self.”

While Katherine acknowledged that we are only able to experience the world from our subjective viewpoint, she said, “Our practice is to keep witnessing limited self. Gradually I learned that even though I can’t see from any perspective but this one, I can include other perspectives, understand that others have their own perspective, and each is just as true and real as mine, even if we’re having a disagreement. That’s a stretch of the heart muscle.”

“Heart in Bloom” by Patrice Vecchione

Writing is one of the most effective ways I’ve discovered to become cognizant of the limitations of my personal point of view and give my heart muscle a healthy stretch.

For example, if I hadn’t sat down to compose an essay about perspective to promote our free upcoming “Write Your Mind Open” workshop, I never would have written about the evolution of my spiritual life, which gave me an important opportunity to reflect on some of my painful and complicated history from my current vantage point, and contemplate what that time might have been like for my parents and sister. I hadn’t planned on diving into this topic, but often when my fingers touch the keys of my laptop, what is waiting for attention in my subconscious begins to pour out, which is part of the magic of writing.

Patrice Vecchione—the extremely wise author, poet and artist who will be leading our “Write Your Mind Open” workshop on February 24—says, “Through writing you can get a fresh perspective on the stories of your life, gain insight into your unique way of experiencing the world, and learn how being in ‘not-knowing,’ which is fundamental to the writing process.”

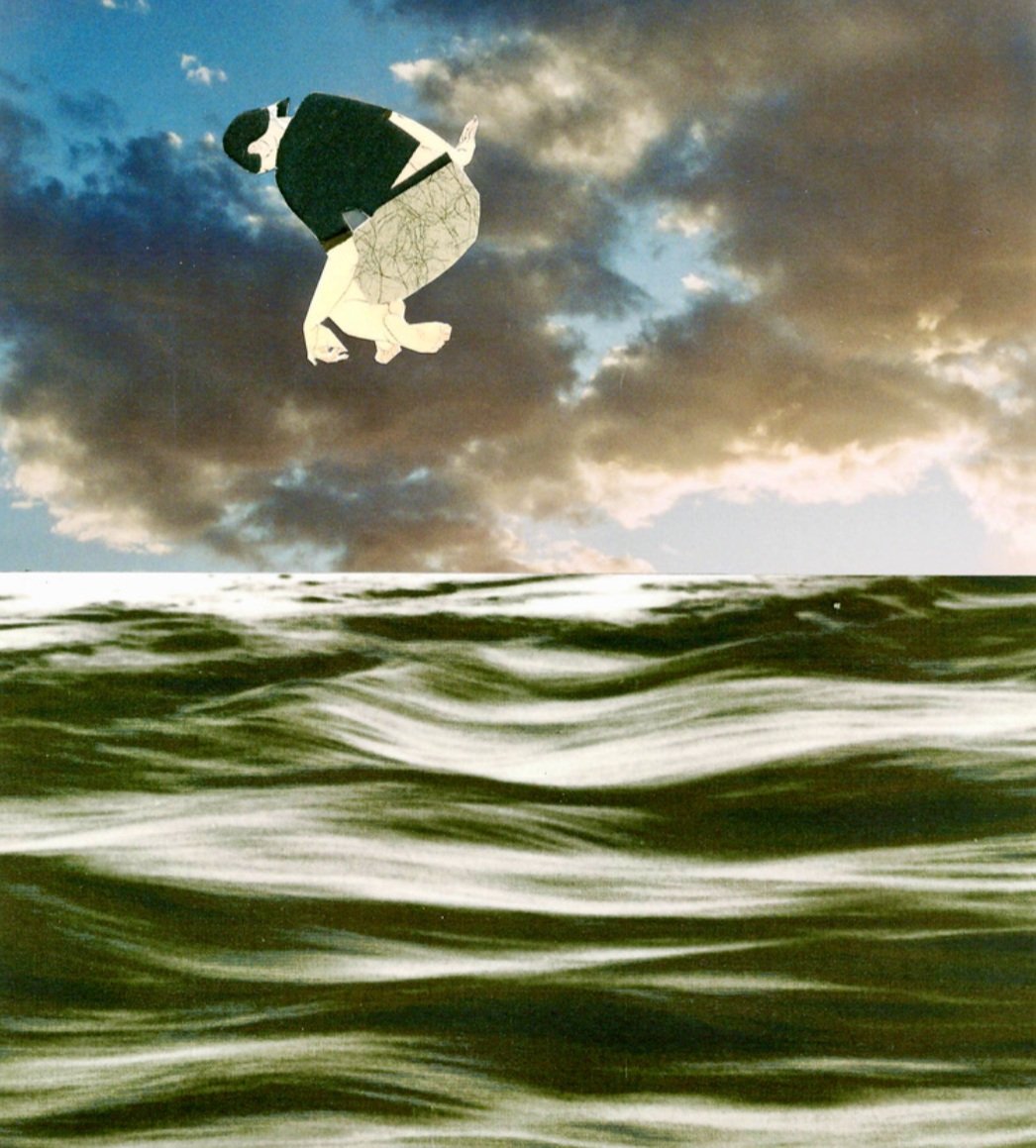

“The Knot Untied” by Patrice Vecchione

During our two-hour online workshop, Patrice will expertly lead us in an exploration of:

Perspective and point of view

Learning to listen beyond your mind to your deepest self

How to develop self-trust when writing

How writing can help you develop your ability to be steady in the midst of chaos, confusion and uncertainty

How to know when your mind needs a timeout and ways to do that

The power of keeping something to yourself and the value of knowing when, why and with whom to share it

The importance of utilizing patience and tenderness

What questions to ask and when to ask them

If you’re ready for an internal adventure that can stretch open your mind and heart, please join us on February 24, from 10:00 AM to noon Pacific. Everyone is welcome. No writing experience necessary!