Honoring a Tragic Legacy

Last week, I wrote about my aunt Bronia’s 90-minute private meeting with President Biden on January 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day. I was very moved by the many people who reached out to let me know how touched they were by the story. Those emails validated that the event was not only incredible for our family—it was also deeply healing for others as well. President Biden demonstrated the powerful impact of genuine empathy, sustained attention, and great respect. By honoring my aunt, the President paid homage to everyone who shares our tragic history.

Images from the @potus Instagram feed of Myra's aunt, Bronia Brandman, with President Biden

Bronia is my father Mendek’s younger sister. Their parents, Ida and Israel, had their first child, Mila, in 1923, my dad a year later, then a second son, Tulek, followed by three daughters: Bronia, Rutka and Macia. At 17, my father was the first family member taken by the Nazis. When the authorities demanded that every Jewish family in their hometown of Jaworzno, Poland supply one able-bodied person to be sent to slave labor concentration camps in Germany, my father volunteered to go so that his parents would not be forced to choose.

From left to right: Mendek, Bronia, mother Ida, cousin Lipa, Rutka, Mila, Tulek and father Israel

In May of 1942, my father was part of a group of forty young men and teenagers from his hometown forcibly separated from their families and led to the railroad station by armed guards. When he was finally liberated after three torturous years of brutality, starvation and heavy labor, my father was the only one of the forty still alive. It’s no wonder he assumed that his entire family had been killed off as well.

But a few months after the war ended, a cousin discovered 14-year-old Bronia alive in Slovakia. He brought Bronia to my father, who was then 20, living in the part of Germany under American occupation. Through Bronia my father learned about the terrible events that led up to the murders of their parents and four siblings in Auschwitz.

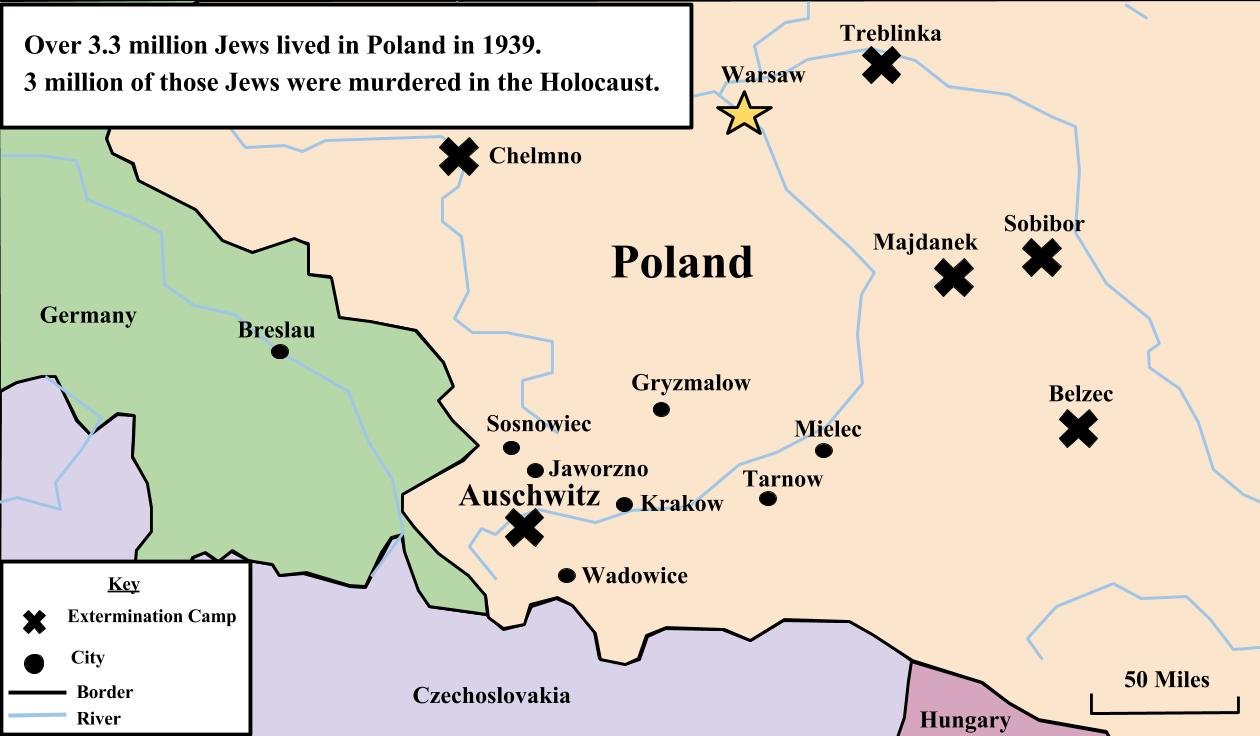

Mendek and Bronia’s hometown of Jaworzno, Poland was only 15 miles from Auschwitz

Until I set out to write my deceased father’s story in Quest for Eternal Sunshine, I knew virtually nothing about my family’s history. It was Bronia who filled in all the gaps, sharing everything she could remember about my grandparents, aunts, uncle and cousins, as well as what life had been like growing up in their very large, close-knit extended Hasidic family.

Today, I’m sharing Bronia’s survival story from Quest for Eternal Sunshine, followed by our family tree which shows which members of our family were killed during the war and who survived. I wrote the book in my father’s voice from his perspective, but virtually all the content from that section came from Bronia. I’m also sharing a 2-minute video of Bronia in which she talks about the final roundup in Jaworzno and how she escaped.

Bronia (front left) with her older sister Mila and younger sister Rutka, 1936

Facing the horrors of the Holocaust isn’t easy. Even after so many years researching and writing about it, it’s still impossible for me to fully believe the magnitude of the atrocities inflicted on millions of innocent people of every age. In her public talks, Bronia must sanitize her descriptions of that horrific time, because the stark truth is simply too shocking for most people to bear.

While it’s not possible for those of us who weren’t there to truly comprehend the living hell the victims of the Holocaust were forced endure, just making an attempt requires much fortitude. Having President Biden spend so much time bearing witness to the unfathomable cruelty and suffering Bronia experienced feels deeply significant and healing.

May we all be inspired to bring hearts full of love and compassion to the world’s suffering so that ancient traumas can begin to heal. May humans evolve in a positive direction by treating each other as equals and always working to foster more kindness, acceptance, and peace.

2-minute video of Bronia talking about the final roundup in her town, and how she escaped.

From Quest for Eternal Sunshine, Chapter 9—Liberation. Pages 39-42

(Bronia’s story written from Mendek’s perspective)

After living in Germany for a while, I was shocked to find out that my younger sister Bronia was alive. Against all odds, Bronia had managed to live through one-and-a-half years in Auschwitz. I couldn’t believe she’d made it. I had been certain that except for a few cousins, everyone in my family had been murdered—my parents, all my siblings, every aunt and uncle.

A cousin of ours discovered that Bronia was alive while looking for survivors on his father’s side of the family. He found her in Slovakia, living with a woman named Bozenka who had saved her life in Auschwitz, and he brought her to me in Germany. Through Bronia, I learned what had happened to the rest of my family.

Not long after I was taken, in the summer of 1942, my family had been ordered to report to the local schoolyard. My parents risked reporting with only two of their children, Tulek and Bronia. My father had told Mila to take our youngest sisters, Rutka and Macia, and go to our family’s hiding place in my aunt’s attic.

After being held all day under the hot sun in the schoolyard, my mother took a risk and told Bronia to try and get away, despite knowing that she might be gunned down before her eyes. Bronia’s experience smuggling probably helped her escape unnoticed. She ran to a Christian neighbor’s farm, where she hid until dark, and then went to find our sisters.

It was too dangerous for the girls to stay in Jaworzno for even one night. The Nazis were completing their final roundup to make Jaworzno Judenrein, “cleansed of Jews,” and Nazi guards searching for Jews in hiding surrounded the entire town. My sisters used back roads to flee to Sosnowiec, which had not yet been made Judenrein. They had no food or water, just the clothes on their backs and one valuable possession: a beautiful hand-knit sweater Mila grabbed on her way into hiding that she later used to save my life.

In Sosnowiec, my sisters slept outside and begged for food until someone told them that children under twelve could get ration cards and be given shelter. But a few months later, all the Jews in Sosnowiec were forced to relocate into the ghetto. My sisters were assigned one tiny, dilapidated room. Soon after, nine of our close relatives found my sisters and moved in with them, so thirteen people shared that one small space.

Jews weren’t allowed to leave the ghetto. When our family began to starve, Bronia had to become a smuggler again. She would sneak out of the ghetto to purchase a live chicken from a neighboring farmer, and then sneak back in, holding it under her shawl. It was a huge risk every time. One noise from the chicken would have alerted the German soldiers and given her away.

My family could never afford to eat the chickens. Instead, they sold them on the black market to get money to buy potatoes and bread, which stretched much farther.

In August of 1943, all the Jews in Sosnowiec were rounded up and packed into cattle cars that took them to Auschwitz. When the train doors opened, German guards with guns, clubs and fierce dogs began screaming, “Out! Out! Quickly! Leave everything behind. Move faster!”

Bronia, Rutka, and Macia were told to go to the line on the left that led directly to the gas chambers. Mila was sent to the line on the right that headed to the forced labor concentration camps. But instead of going where she was told, Bronia ran after Mila.

Immediately upon arrival, my sisters were stripped naked. Male inmates shaved their entire bodies until they were bald, and then their arms were tattooed with prisoner numbers.

Mila and Bronia worked long days on only one bowl of watery soup and a slice of bread made mostly from sawdust. In the barracks, they slept crowded together on wooden planks with just one thin blanket for many women to share, despite the freezing Polish winters. There was no way to get clean, and only one latrine for hundreds of people. Before long, Mila and Bronia became skeletons covered with lice and sores from scratching.

After a few months, Mila came down with typhus and could no longer do heavy labor. She was sent to the Revier, the barracks where sick people were housed in terrible conditions without any medical care. Bronia went with her.

Then a day came when all of the sick and dying prisoners were to be collected and sent to the gas chambers. Bozenka—the Jewish nurse in charge of the barracks who had been one of only three prisoners out of a thousand to survive her transport from Slovakia—risked her life to save Bronia. She pretended that Bronia was her sister so that she had a reason to keep her off the list of those being taken away.

Bozenka continued to care for Bronia when she became so sick with typhus that she went into a coma for a long time. Bronia was still terribly ill during the Death March in January 1945. Bozenka carried Bronia whenever she couldn’t keep up to prevent her from being shot. After liberation, certain that Bronia was an orphan with no family remaining, Bozenka brought her home to Slovakia and enrolled her in school there. She would have kept Bronia forever if our cousin hadn’t found her.

***

Bronia and I had suffered terribly and lost so much that neither of us could put our pain into words, not even to each other. We’d both witnessed unthinkable horrors that could never be erased. The memories of what we’d lost forever were both precious and torturous. Except for each other, everything we loved had been destroyed. Parts of us had been destroyed as well.

We had no idea how difficult it would be to live with what had happened. Bronia felt guilty for being alive. She couldn’t stop thinking about Mila or our two baby sisters dying alone in the gas chamber without her there to hold their hands.

Neither of us knew how to move on. We had nothing to look forward to, just anguish and devastation to run away from. Although we’d survived, living without a home or family in a world full of unfathomable cruelty did not feel at all like a triumph.