The Stories We Carry

We all carry stories that are the “greatest hits” of our personal history—narratives about our family, major events we experienced, and pivotal choices that changed the trajectory of our lives. Some empower us with confidence and optimism, while others haunt us, stifle our growth, or prevent us from pursuing what would bring us great joy.

Many of these stories, particularly the traumatic ones, have played on repeat for decades. They are often outdated, which essentially imprisons us in the past. And because we often mistake these narratives for absolute facts, they can narrow our perspective and lead us to pigeonhole people—including ourselves.

Psychologists once believed memories were permanent—that therapy could help you cope with difficult ones, but not change them. However, recent science offers a hopeful new perspective on healing and personal growth through a process called memory reconsolidation. It turns out that when we revisit a memory, it enters a flexible state where we can weave in new insights and feelings of safety that transform its emotional core.

Decades before this research, my father Mendek Rubin discovered the malleable nature of his own habitually held stories in his search for healing. As a Holocaust survivor with a tremendously traumatic history, taking advantage of this phenomenon became a cornerstone of his journey from darkness to light. He wrote, “For most of my life, I had no clue that a new script was in order. I didn’t even know that I was allowed to make that request. But finally, I came to realize that I could and should figure out how to write a new story. It’s never too late.”

When my father made it his top priority to closely observe how his mind worked, he began to notice that it functioned as a storehouse for all of his self-defeating memories and beliefs. “Although I thought I was constantly having fresh experiences,” he wrote, “More often than not, I was thinking, feeling, and reacting to those experiences in predictable, automatic ways. My unconscious mind was projecting memories from my storehouse onto the outside world, which is why my perceptions remained unchanged. It quickly became clear that I didn’t control my thoughts. They controlled me.”

My father realized that in order to give up fear as a way of life and write a new, more joyful, peaceful story for himself, he’d have to explore his long-avoided history, no matter how difficult the process was. Going back in time to relive events that had taken place so long ago was extremely painful, especially at first. “For my entire adult life, my childhood had been off limits—a secret, forbidden region I dared not enter. I was terrified to remember my boyhood, and had blocked almost all of those memories. The few I had retained were virtually all grim, which only served to reinforce my unhappiness.”

Fortunately, in addition to his grimmest memories, my dad was able to recall some delightful ones. Each of these felt like uncovering buried treasure.

Mendek (far left) with his family in Poland—all of whom were killed in the Holocaust except for one sister

My father wrote, “When I looked back at my childhood through new eyes that searched for everything good, I was surprised to discover that I’d completely forgotten about so many pleasant experiences. I began to regularly bring myself back in time to conjure up the people I’d loved, the tastes of my favorite foods, activities that had once delighted me, my youthful hopes and dreams. My intention was to feed my mind and heart with these memories until they became indelibly impressed into my consciousness.”

Each time my father recalled a pleasant memory, he’d write about it, and then review it over and over again. This was one of the ways he was able to finally rekindle an inner sense of safety and love that had been extinguished by the war—a new inner orientation that made the outside world look like a much brighter and happier place.

In the seventeen months since my mother’s death, I have been stunned by the mutable nature of my own memories. For the first time—as a woman past sixty—I’ve been able to view my mother through more “honest eyes.” I’ve finally been acknowledging her emotional volatility and the many ways she failed me when I was growing up—truths I’d repressed for decades out of a deep-seated fear of her anger and rejection. For my entire life, I stayed safe by burying my own reactions and attempting to be the perfect daughter.

As I’ve allowed my own long-denied pain, anger, and confusion to surface, my stories about my mother and our relationship have begun to shift. By being candid about her faults, emotional blocks are finally clearing, allowing me to access a different layer of memory.

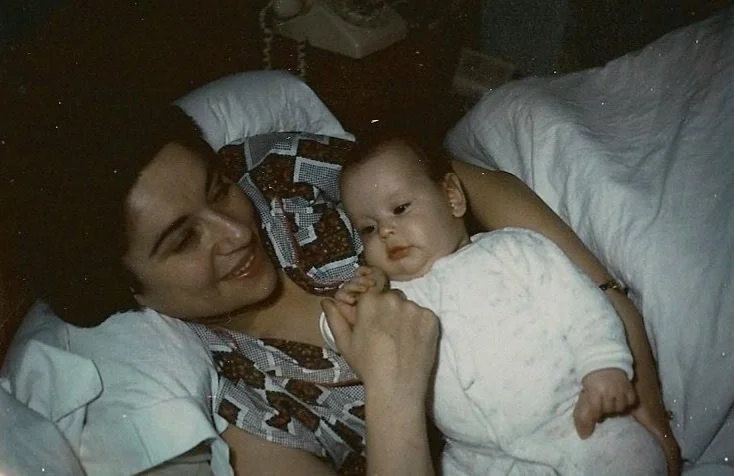

These days, I’ve been recalling the genuine affection my mother showered upon me, and her innate glory that was so often cloaked by her own immense, unhealed trauma. I’m able to tune into her light and love, which feels wonderful.

Baby Myra with her mother Edith

Patrice Vecchione—the author, teacher, and artist who will be leading our free “Write Your Life Open” writing workshop on February 21—explains that writing is an extremely effective way to explore and update our old narratives. “When we unpack our familiar stories and look at them from different angles, what we discover is usually different from what we initially expected. Often, simply taking a second look at old tellings reveals glimmers of light and veins of gold. By engaging the enormous power of the pen paired with imagination, doors you thought were locked forever may suddenly and easily open.”

An important benefit of realizing how malleable our personal stories are is that we begin to see that the narratives we inherited from the wider world are equally flexible. So many of the “fixed facts” we believe about other people or different cultures are actually antiquated scripts that do not serve understanding, empathy, or compassion. When we pick up the pen to “write our lives open,” we can do something revolutionary: actively disarm the rigid beliefs that fuel conflict in ourselves and in the world around us.

As my father wrote, “Our beliefs can become weapons we aim at other people and at ourselves, and a threat to them can feel like a threat to our very lives. The power of stories to create good and evil should never be underestimated.”