Healing from the Holocaust

By Myra Goodman

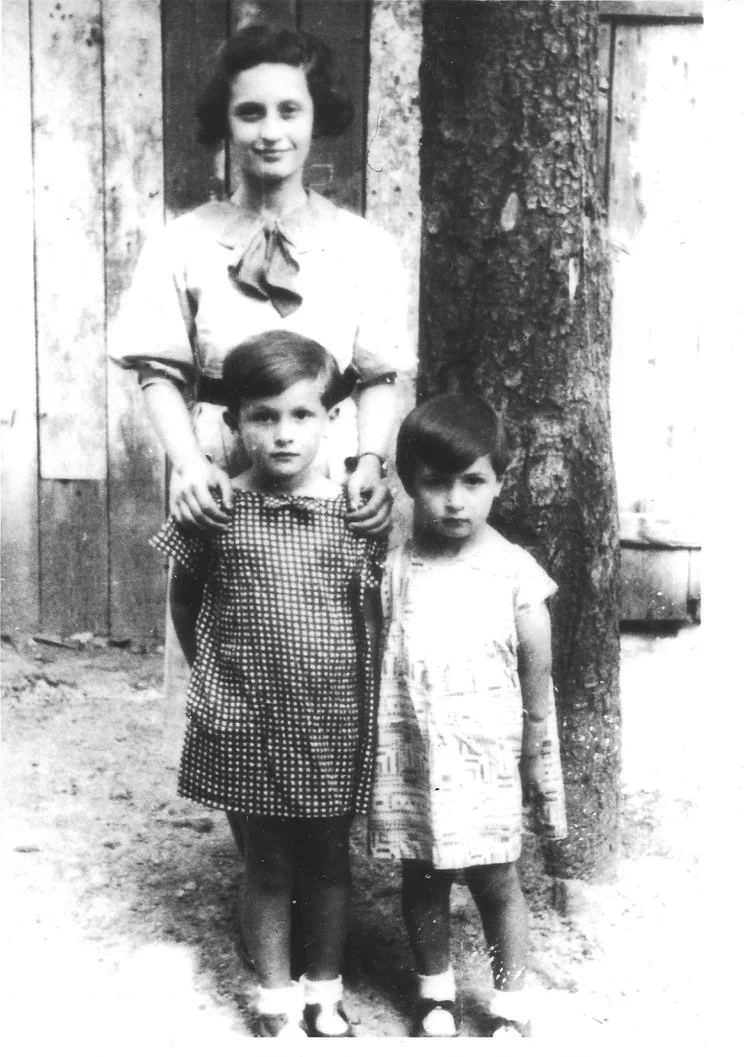

My Father’s Story

My father, Mendek Rubin, was a quiet, sensitive, and imaginative boy. He was born in 1924 into an Orthodox Jewish family in a small town in Poland, where the Jews were viewed as intruders with alien customs and treated with suspicion and contempt. My dad felt this animosity strongly as a child. He had stomach aches every morning because he feared the Polish children who would often throw rocks at him on his way to school.

When World War II started, cruelty against Jews was institutionalized and encouraged. Public humiliations became commonplace and prohibitions were enacted that were both dehumanizing and crippling. By the end of 1940, all Jewish valuables had been confiscated and Jewish businesses seized.

In 1942, at seventeen, my father was sent to a Nazi slave labor concentration camp, where he survived three years of unimaginable cruelty, starvation, and relentless hard labor. When he was finally liberated, he had to face that his parents, four of his five siblings, and most of his extended family had been brutalized and murdered. Almost his entire world had been destroyed. For decades after liberation, my father suffered from unrelenting depression, feelings of fear and isolation, and terrible recurrent nightmares.

Healing is Possible

In her book, Wounds into Wisdom — Healing Intergenerational Jewish Trauma, Rabbi Tirzah Firestone, PhD writes, “Jews and all peoples who have suffered the traumatic effects of degradation and displacement, racial oppression and violent persecution simply for being themselves, must wrestle with their legacies. The past can be cause for fatalism, hypervigilance, and a sense of radical unsafety in the world.”

So how is it possible to mend from a trauma as massive and horrific as the Holocaust?

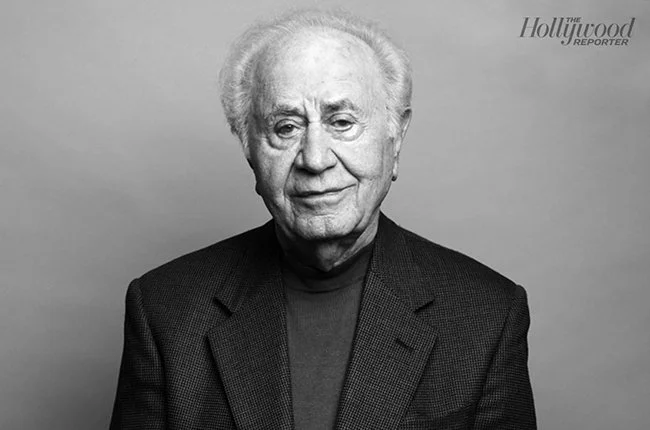

Remarkably, my dad was able to heal himself enough to live a joyous and fulfilling life. In fact, he became the happiest and most peaceful person I have ever known. But it wasn’t until I found his unfinished manuscript in 2013, the year after he died, that I learned for the first time how he was able to accomplish such a feat.

A brilliant inventor who used his mechanical genius to uncover the secrets of his own psyche, my father spent much of his life trying to decipher how our belief systems are created and the dangers they can pose. He wrote, “Ever since I was a young man, I’d sensed that human beings were creatures of arbitrary habits. At the end of the war, when I looked into the eyes of a German soldier my age, I’d been surprised to recognize our common humanity. More than our uniforms and ethnicity, what separated us was our conditioning. If the two of us had been raised by the other’s parents in the other’s hometown, it’s likely I would have been the soldier carrying the gun and he the starving, brutalized inmate.”

Mendek said that every inhumane act begins with a thought, and that “peoples’ thoughts can sync, so that they pounce on their prey like a pack of wolves.” Nonetheless, he grew to believe that there are no bad people, only bad ideas. After spending so much time with my Dad’s writing and philosophy, I have gained a deeper understanding of his healing process.

Mendek’s Healing Process

Mendek acknowledged his pain and emotional problems, and became committed to finding a solution (this began in his early 40s).

With help from traditional and alternative therapies, Mendek began to explore and face his memories and experience the intense emotions — shame, grief and fury, as well as love — that he’d been suppressing his entire life.

Mendek observed his mind and his reactions closely and saw how his past was determining his present — that he was habituated to feel pain, not pleasure. To give up suffering as a way of life, he needed to write a new “script” that would foster feelings of peace and joy. “It’s never too late!” he said. Through self-observation, he also developed a “witness consciousness”—the awareness that he is not his thoughts and emotions, and was capable of changing them.

Mendek decided that, “No matter how troubled the outer world appears to be, I have the power to decide that a loving universe will exist for me.” He worked diligently to established new thought patterns by utilizing visualizations and affirmations, feeding himself a steady diet of positive thoughts to create new grooves in his mind and shift his awareness to the positive, increasing his capacity to enjoy his life.

Mendek fostered boundless self-love, embraced his inner child, and learned to let go of his enslavement to societal expectations, which created a safe and pleasurable internal environment where his natural inborn joy could begin to flourish. Mendek grew to believe that, “Loving myself, just as I am, is the most important act of kindness I can perform on this planet.”

Mendek realized that when he maintained a victim mentality he was living in the past as a prisoner of his own hatred and was unable to fulfill his own destiny. He learned to live in the present moment, where he was able to reconnect to what he called “The Divine,” which made him feel supported by a loving universe — spiritually, emotionally and physically nourished. He wrote, “I believe we are all children of a benevolent cosmos, and at the core of our being, each one of us is the divine individualized. Everything is made of energy; nothing is isolated. We are all connected by love, and our heart as our center of gravity is always our truest and most helpful guide.”

My dad felt certain that focusing on changing ourselves is more important and effective than trying to change the world. We need a total shift in consciousness — one person at a time — or the past will just keep on repeating itself. He wrote:

“When I meet a German person now, my intention is to no longer let my vision be colored by my baggage from the past. Instead of automatically associating him with my worst memories, I remember that despite everything, his essence is pure. Just like me, he was born perfect. Just like me, he learned through imitation, repetition, and force of habit.

Now, when I meet a German, I meet him in the present moment. In this moment, he is just a person. I deliberately make myself look at him with fresh eyes. It’s a conscious act. I do it because it’s what I’ve decided I want to do. I don’t do it for him. I do it for me.

It’s not that I deny the past. I just don’t live in it. When I look at the world through the eyes of the past, I am miserable. But when I live in the now, unhappiness doesn’t exist, because I’m not keeping it alive inside of me.”

My Journey

Although I didn’t personally live through the Holocaust, as a second-generation survivor, I inherited a legacy of silence, insecurity, and fear. I feel affected and shaped by it in countless ways.

Additionally, because the beliefs and political conditions that led to the Holocaust are not safely confined to history, healing is all the more challenging. In September 2019, the United Nations released an alarming report on anti-Semitism, which acknowledged that violence against Jewish individuals and sites worldwide is significant and increasing. The report also said that “anti-Semitic hate speech” is particularly prevalent online. This reality reinforces the feeling of being misunderstood, unfairly hated, and at constant risk of emotional and physical attack.

Two of the hallmarks of trauma Firestone discusses in her book that I most identify with are disassociation (feeling numb or split off from ourselves), and hyper-arousal (when our emergency fight or flight response remains chronically activated).

With my dad as my biggest inspiration and one of my greatest teachers, I have embarked on my own trauma healing journey, and I’ll be continually sharing the resources I discover along the way on this website.

Intergenerational Trauma

One thing I’ve learned is that trauma responses do not only result from first-hand experiences. They are also passed down from parents and extended family by trauma-induced behaviors and collective memory. Additionally, numerous scientific studies have confirmed that trauma can also be passed down through our bodies by changes in how our genes behave, confirming that catastrophic events can alter the body’s chemistry and that these changes can transmit to the next generation.

Lucky for me, in addition to the tragic history I inherited from my father, he also left me a legacy of strength, perseverance, and awakening—a commitment to breaking the cycle of anguish, hatred and fear. Mendek had a deep desire to share his revelations with the world, and it has become my mission to pick up where he left off.

One of the biggest gifts I got from my dad is the understanding that it’s possible to be happy in a world where the Holocaust happened. Such unfathomable horror and a beautiful universe can exist simultaneously — one doesn’t preclude the other. Another huge gift was the permission to let go of my suffering. Being loyal to my ancestors doesn’t mean that I always have to imagine and carry their pain.

I now know that the best way to honor my father is to fully appreciate myself and delight in being alive.

If Mendek could find his way back to love, the potential must exist for all of us.

The journey continues!

Start the Journey

See resources for healing from trauma.

Learn about the experience of living through the Holocaust.

Read Mendek’s story in Quest for Eternal Sunshine.