Feed Yourself a Steady Diet of Joy and Optimism

Lessons From My Father

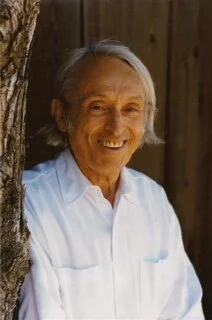

My father once said, “You have to be as careful with the thoughts you think as you are with the food you eat.” As an organic farmer and cookbook author—someone who spent decades passionately promoting the benefits of healthy organic food—this statement immediately caught my attention.

Before I submerged myself in my father’s words, I might have debated the concept. Now, I wholeheartedly agree. My dad’s writings convinced me that the world I see is not an objective world. Rather, it is a world that reflects my own projections, determined by my unique conditioning and previous experiences. Everyone sees the world differently, and what we see often changes over time, or even with our particular mood.

Through self-observation, my father noticed that his mind functioned as a storehouse for all his memories, beliefs, and emotions. Although he assumed he was constantly having fresh experiences, more often than not he was on autopilot, unconsciously projecting memories from his storehouse onto the outside world. He concluded that this was why he was trapped in a deep-rooted cycle of fear and pain.

My father explained how dysfunctional it is to consider our beliefs to be facts, when in truth, they are totally arbitrary. He asked himself questions like, “If I’d been born into a different culture, would my values, world outlook, and personality be the same? What if I’d been born on a different continent, into a different race or religion?”

Experimenting with his own mind, my father realized that the origin of the information being fed into his brain really didn’t make a difference. Whether he was having a fantasy or an actual experience, happy thoughts made him feel happy, and disturbing thoughts caused worry and upset. He decided to build an inventory of new, joyful thoughts and experiences the same way he’d have learned how to play the piano: through practice and repetition.

My father’s strategy was effective. When he changed the type of information he put into his brain, be began to feel calm, connected, and joyous more often. “The benefits of thinking positive thoughts were immediate,” he wrote, “which inspired me to feed myself a steady diet of them.”

My dad’s explanation about how human minds work has helped me understand myself better, and it’s also helped me make better sense of the wide divisions in our country today—how prejudices are formed and why they are so hard to break.

Changing our beliefs is a huge challenge, like swimming upstream against a very strong current. But my father proved that with persistence and perseverance, it’s possible. Once he began to feed himself a steady diet of positive affirmations, he never stopped.

In my own life, I’ve recently taken on this practice. It helps to say the affirmations in the present tense, as if they are already true (such as, “I am strong” versus “I am getting strong”). I’ve found the key to making affirmations have a truly transformative effect is to truly feel them as truths in my body. When my positive affirmation is, “I am strong,” I need to actually feel that strength in my limbs, torso, and mind—I need to digest it, as I would a nourishing food.

Incorporating affirmations into my life implies both faith and optimism—wonderful qualities I want to strengthen—and they make me feel more empowered. As my father once told me, “Fear feeds on fear and happiness feeds on happiness.” As a farmer, I learned long ago that the seeds you water and care for are the ones that grow and blossom.

Want to try this for yourself? Here are some of Mendek’s affirmations. Choose one that resonates with you, and repeat it to yourself today.

If you are interested in the science behind why Mendek’s techniques to change his mind worked so effectively, this short video (only six minutes) from Dr. Joe Dispenza titled, Neurons that Fire Together Wire Together, gives a great overview on how whenever we make our brain work differently, we are changing our minds.

Mendek was an extremely curious, imaginative, and inventive person from the time he was a young boy. At only seven, he devised a key that could open any lock. His family owned a hardware store in their small town of Jaworzno, Poland, and if someone accidentally locked themselves out of their home, Mendek was the one sent to open the door.

During WWII, he and his family endured years of crippling prohibitions, cruelty and terror. At seventeen, my father was sent to a Nazi slave labor concentration camp, while his parents and all but one of his five siblings was murdered in Auschwitz.

My dad immigrated to America in 1946 as a penniless orphan with only a sixth grade education, yet his inventions eventually helped revolutionize both the jewelry and packaged salad industries. Eventually, in his quest to escape a life of vast loneliness, fear and unrelenting depression, he focused his genius on mending his own psyche.

After my father died, I learned from writings he left behind how a man with his horrific history had managed to become the happiest and most peaceful person I have ever known. Just like the universal key he’d invented as a child, my father discovered the keys to freeing himself from the psychological prison he’d been trapped in for decades to find his way back to love.

My father hoped his discoveries could help others on their own healing journeys. I continue to learn from him every day, and I’ve written about some of the keys to happiness he’s been teaching me—a series of nine essays that start today.

Thank you for your interest in my dad’s story and wisdom.